The Western Australian Museum is currently hosting a display of the terracotta warriors of Ancient China, with this exhibit running from 28 June 2025 to 22 February 2026. Well known for being set in place to watch over the tomb of the first emperor, Qin Shi Huang (秦始皇; 259–210 BC).

As with most such displays, room lighting was dim and flash photography was prohibited—both measures to minimise the damage to the artefacts from exposure to light. I brought along my old Nikon D70S (which has a quiet and gentle-sounding shutter mechanism) and Nikkor AF-S 18–70 mm f/3.5–4.5 lens. A standard zoom lens with stabilisation is a significant omission from my photographic kit, but over the last several years I mainly been shooting with other lenses anyway.

The 18–70 mm is not stabilised, so I relied on a range of mitigating measures: (1) opening up the aperture as much as possible, though that generally meant just f/4 or f/4.5; (2) boosting ISO sensitivity, for which I felt ISO 800 was the best compromise between image quality and faster exposure durations; (3) stabilising myself against a wall while shooting; and (4) shooting multiple frames, so that I could pick the best frame while post-processing. All in all, the results were not too bad, but a stabilised lens would have allowed for much better results.

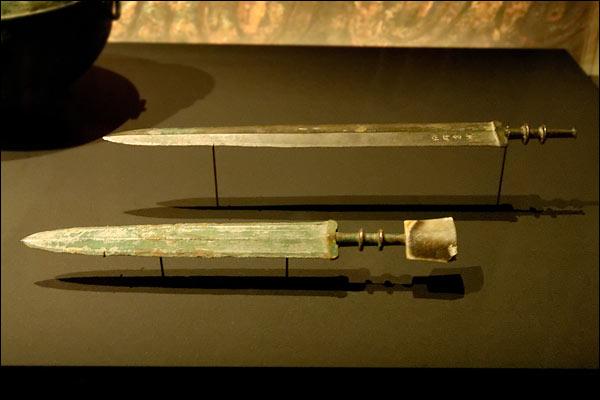

We start with a couple of bronze swords dating back to around 475–221 BC, according to the notes accompanying the display. Chinese swords of this period distinctly lack any form of crossguard, and can look somewhat odd if you are used to seeing mediaeval European swords. I first came across this design in historical Chinese movies and, to my eye, there is a certain elegance to them; they are almost like sleek, unadorned spearheads more than anything else.

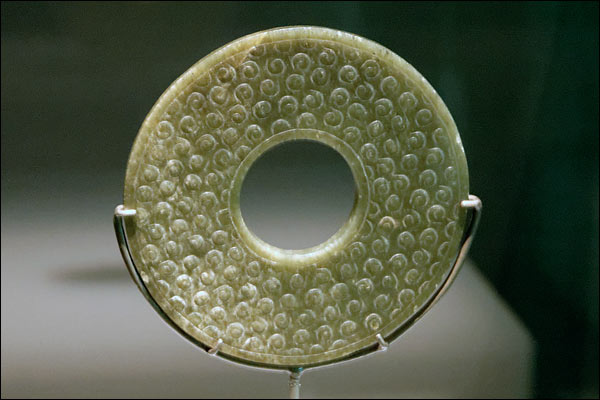

Next we have an ornately-crafted pendant made from grey-green jade (c. 475–221 BC), a disc which is somewhat greener in tone (475–221 BC), and a couple of brass doorknockers (c. 206 BC–AD 9). Even though I am showing these artefacts at a low resolution and shot these images from a little distance away (and through a protective glass barrier), you can see the fine detail that the artists carefully shaped in their work.

The first actual portrayal of a warrior we see is this infantryman (c. 206 BC–AD 9). When newly completed, this piece would have been holding a weapon, possibly a polearm of some kind, in the right hand.

These bronze rabbit ornaments are estimated to have been from around 770–476 BC, so are somewhat older than the previous artefacts shown above.

The clay cavalry statues and gold flower ornament below are both estimated to be from around 206–9 BC. The cavalry were smaller than life-sized.

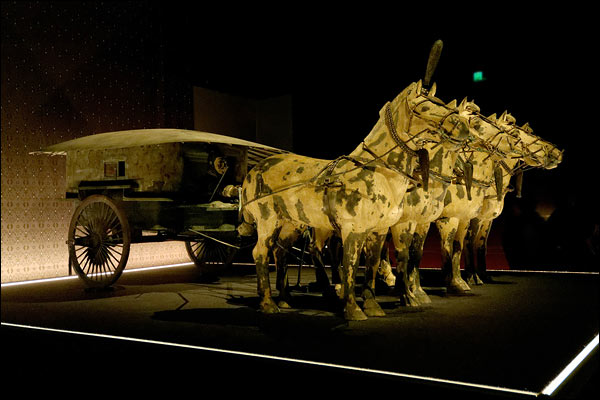

These two chariots (c. 221–206 BC) are close to life-sized representations, showing vehicles that formed part of the imperial entourage. I believe that these may be replicas, with the original restored creations remaining in China. In any case, the craftsmanship is remarkable.

This representation of an attendant (c. 221–206 BC) is the first actual terracotta creation I am showing here; terracotta is a specific type of pottery with a higher iron content and some differences in the firing process, as I understand it.

One of the most striking pieces in the display was this bronze swan (c. 221–206 BC). You can get a slight sense of the amount of detail in the craftsmanship even in this small image below, but what caught my eye when seeing it was the perfect form and proportions; rather than being some object made by human hands, it may as well have been an actual swan, frozen in time.

Next is probably one of the more well known terracotta figures—an archer, kneeling at the ready. I believe this figure has been featured widely in publicity materials over the years; I immediately recognised it when I came across it.

One of the most distinguished-looking items on display was this terracotta statue of a general. This artefact seemed not only slightly larger in physical size than the other terracotta warriors, but also appeared to have been made to a higher standard (unsurprisingly). Note, for example, the smoothness of the surfaces and the detail in the moustache and beard in the second photograph below. I did not see this level of refinement in the other terracotta warriors that I saw.

The terracotta horse (c. 221–206 BC) below was not quite life-sized, but larger than the cavalry statues shown above.

Also on display was some stone armour (c. 221–206 BC), with small shaped stone segments held together with bronze wire. As with the swords shown earlier, you can see this style of armour in historical movies. It bears some superficial visual similarity to some European armours, but is distinct in having square and rectangular pieces rather than scale-shaped pieces.

We finish as we began—with a sword. In this case, though, we have a much larger weapon; a two-handed bronze sword (c. 221–206 BC). The overall design appears to be the same (no crossguard) as for the previous blades, but the proportions are obviously different.

All in all, the exhibition is well worth a visit if you are interested in this era and place in history.